Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a devastating disease. Despite decades of research, science has not pinned down causes or discovered highly effective treatments. And while a healthy diet, regular exercise, and other measures can help people slow or avoid AD, we badly need more routes for preventing it.

That’s why a new study is so intriguing — and potentially game-changing. Researchers have found that the risk of death due to AD is markedly lower in taxi and ambulance drivers compared with hundreds of other occupations. And the reason could be that these drivers develop structural changes in their brains as they work.

Drawing a connection between Alzheimer’s disease and work

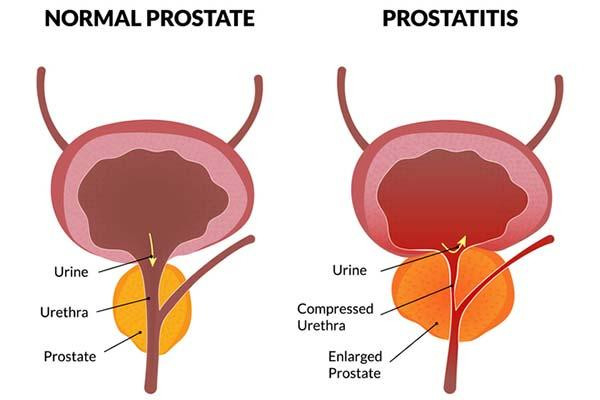

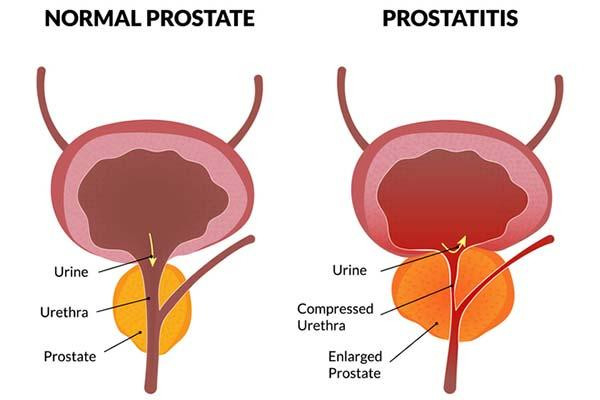

In the past two decades, small studies demonstrated that London taxi drivers tend to have an enlargement in one area of the hippocampus, a part of the brain involved with developing spatial memory. Interestingly, that part of the brain is one area that’s commonly damaged by AD.

These observations led to speculation that taxi drivers might be less prone to AD than people with jobs that don’t require similar navigation and spatial processing skills.

A recent study explores this possibility by analyzing data from nearly nine million people who died over a three-year period and had occupation information on their death certificates. After accounting for age of death, researchers tallied Alzheimer’s-related death rates for more than 443 different jobs. The results were dramatic.

What did the study find?

- Taxi and ambulance drivers were much less likely to die an AD-related death than people in other occupations. AD accounted for 0.91% of deaths of taxi drivers and 1.03% of deaths of ambulance drivers. Among chief executives, AD accounted for 1.82% of deaths, which is close to the average for the general population. While these differences may seem small, they translate to more than 40% fewer deaths related to Alzheimer’s among taxi and ambulance drivers.

- This benefit did not seem to extend to others with jobs involving navigation. For example, aircraft pilots (2.34%) and ship captains (2.12%) had some of the highest rates of death due to AD. Bus drivers (1.65%) were closer to the population average but still not nearly as low as taxi and ambulance drivers.

- Other types of dementia did not follow this pattern. Rates of death due to dementia other than AD were not lower among taxi and ambulance drivers.

Why would driving a taxi or ambulance affect the risk of AD-related death?

One possible explanation is that jobs requiring frequent real-time spatial and navigational skills change both structure and function in the hippocampus. If these jobs help keep the hippocampus healthy, that could explain why AD-related deaths — but not deaths due to other types of dementia — are lower in taxi and ambulance drivers. It could also explain the older studies that found enlargement in parts of the hippocampus in people with these jobs.

And why aren’t bus drivers, pilots, and ship captains similarly protected? The study authors suggest these other jobs involve predetermined routes with less real-time navigational demands. Thus, they may not change the hippocampus as much.

What are the limitations of this study?

A single research study is rarely definitive, especially an observational study like this one. Observational studies can only identify a relationship — not establish a firm cause — between a protective factor and a condition like AD. There could be other explanations for the findings. For example:

- Information on death certificates. Researchers in this study used “usual occupation at the time of death” as provided by a survivor presumed to know that information. But that might not be accurate. And many people have more than one job over the course of their lives.

- Self-selection. Perhaps people who are prone to AD find navigation more challenging than others, and so tend to avoid these occupations. Similarly, it’s possible that people who are less prone to AD tend to have better navigational skills and are more likely to pursue jobs for which that’s an advantage. In this way, self-selection, rather than the occupation itself, could have contributed to the study’s results.

- Confounders. The study’s findings could be due to factors other than those assessed by the study (confounders). For example, it’s possible that people whose lifelong occupation is driving a taxi or ambulance are less likely than others to smoke. Since smoking is a risk factor for AD, the lower rate of smoking, rather than the occupation, could contribute to fewer AD-related deaths among these drivers.

- Chance. The findings could be due to chance, especially because there were just 10 AD-related deaths among taxi drivers. Even a small number of overlooked deaths due to AD could sway the results.

And even if driving a taxi or ambulance could lower your risk of AD-related death, what’s the impact of GPS technology now in widespread use? If these jobs now require less navigational demand due to GPS, will the protective effect of these jobs evaporate?

How might this new study help you reduce your risk of AD?

You might wonder if these findings can be applied to anyone who wants to lower their risk of AD. For example, could outdoor treasure-hunting activities that require complex navigational skills, such as orienteering and geocaching, help stave off AD? At least one small study found that orienteering experts had better spatial memory than orienteering novices.

Could puzzles, video games, or even board games designed to build spatial skills reduce the risk of AD? Think Rubik’s Cubes and jigsaw puzzles, Minecraft and Tetris, chess and Labyrinth. A round of Battleship, anyone? And if these activities are actually helpful, how often would you need to play?

I look forward to the results of studies exploring these questions. Until then, it’s best to rely on experts’ recommendations to reduce your risk of AD, including high-quality sleep, diet, and regular exercise.

The bottom line

I find this new research about taxi and ambulance drivers having lower rates of AD-related death fascinating. Considering how often we hear about the risks of certain jobs, it’s encouraging to hear about occupations that might actually protect you from disease.

If confirmed by other research, the results of this study could lead to a better understanding of Alzheimer’s disease — and, more importantly, how to prevent it.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD Share